By Gary Gunderson

An institution dedicated to healing is naturally nice to people when they are patients. And a leading academic research institution such as Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center is smart about the diseases of its patients. But there’s some new 21st century creative magic happening at Wake Forest Baptist—developing roles outside hospital walls with sensitivity and intelligence to the lives of people before and after they are patients.

Life intelligence of the community

The business of health care is turning upside down and inside out. Those who pay the bills — mostly the government (through Medicare and Medicaid) and private insurers — are getting tired of paying for service one episode at a time. They don’t like paying for this pill and that procedure and that visit. They want to buy health rather than just a long list of disease services.

As a result, in the new economics of health care, the focus is shifting away from selling more medical services. This requires hospitals to get smarter about some things they never had to think about before, namely what is going on in the lives of patients before and after they are in the hospital? And who else besides the hospital cares about them enough to help?

Most important, how can the hospital blend its enormous scientific intelligence with what we’ll call the life intelligence of the community?

Most important, how can the hospital blend its enormous scientific intelligence with what we’ll call the life intelligence of the community?

Closing the gaps

Much of the current strategy of FaithHealthNC traces back 30 years, to The Carter Center in Atlanta and a profound meeting held in 1986 by President Jimmy Carter. Considering what to do with the rest of his life, former President Jimmy Carter hosted a large meeting of global health experts with a profound question: how much of the burden of premature death could be prevented based on what we already know?

Called “Closing the Gaps,” that meeting realized what many people already knew: about two-thirds of all death before age 65 is due to factors that could be prevented or managed. But by whom? By each of us and those who care about us — our family and close social networks, including the faith institutions we belong to or who are near enough to care about us.

President Carter and his close friend, Dr. Bill Foege, convened a few hundred religious leaders to see if they could understand this stunning prevention opportunity. They then created the Interfaith Health Program in 1992 funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in close relationship with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Connectors: the cutting edge

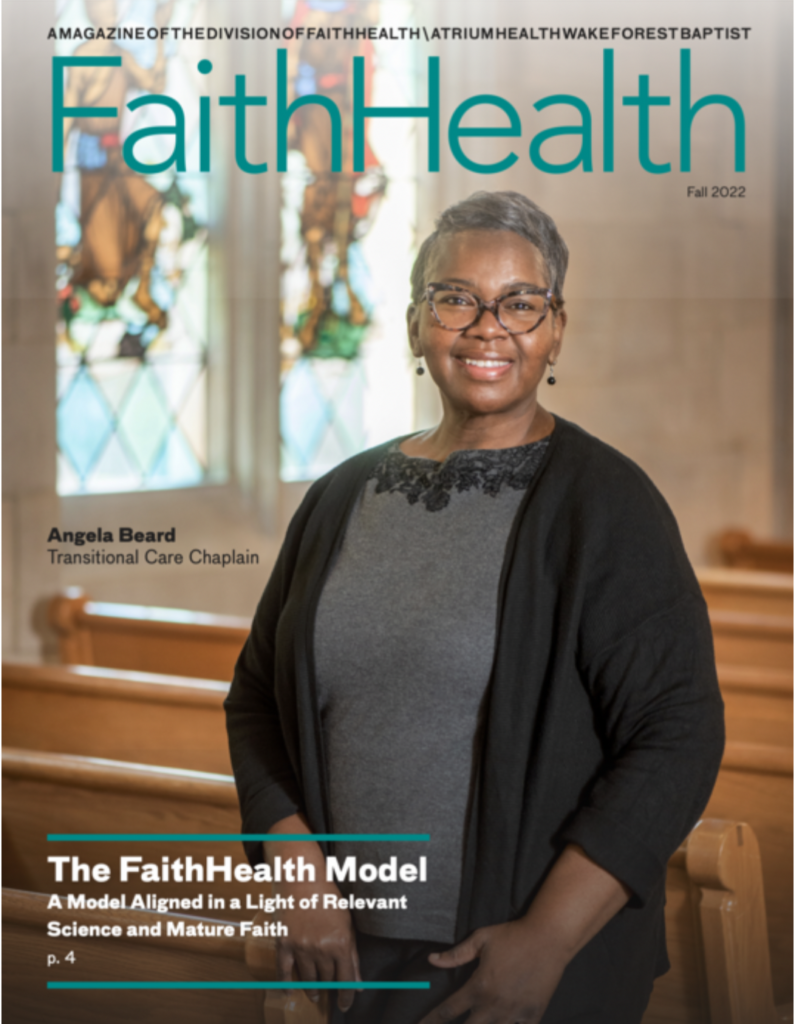

The reason to tell even this much now is to underline that when you see the beautiful caring faces of FaithHealth Connectors, you are looking at the cutting edge of 21st century health science.

T he Connectors embody the answer to that simple revolutionary question asked in 1986. Smart science becomes dumb and, worse, arrogant, without bridging relationships of trust. The length and quality of our years literally depend on whether anyone will be with us in our inevitable times of dependency. Science has no chance until love finds a way to cross over the last few feet and inches of human disconnection.

he Connectors embody the answer to that simple revolutionary question asked in 1986. Smart science becomes dumb and, worse, arrogant, without bridging relationships of trust. The length and quality of our years literally depend on whether anyone will be with us in our inevitable times of dependency. Science has no chance until love finds a way to cross over the last few feet and inches of human disconnection.

In the 21st century, most of us are much more disconnected than is healthy. And most churches are no more connected to their surrounding neighborhoods than are hospitals. Any honest pastor will tell you that in the modern American church, most “members” are strangers to each other about most of the things that matter.

The most important medicine is connection. Hence, Wake Forest Baptist has invented the role of Connectors, people whose job is to reach the isolated and disconnected. They are drawn from the social networks within caring range. They are not designed primarily for those within active caring networks, such as congregations.

Rather, Connectors are designed for the tough and lonely streets where science is overmatched by isolation, anxiety and fear. You don’t send Connectors out alone or untrained. They rest on a body of careful, thoughtful work decades in the making. They meet quarterly for continued training and are themselves cared for by supporting staff.

Best medicine is connection

This kind of medicine is new and relatively inexpensive. It works with the social body — the love and care that is natural in communities. But we are not in a healthy social body these days, so we have to plant some new social healing roles, especially in those places where isolation is winning the day.

We pay Connectors to enable their work. Because their work tends to prevent high cost hospitalization, we can afford to deploy many Connectors and aim them into any community where our data shows a pattern of high emergency room use for conditions we know can be treated in lower cost settings. We call that proactive mercy, and the Connectors are the precision tools designed for just that. To date, the Connectors have had more than 1,300 encounters with people in need.

We pay Connectors to enable their work. Because their work tends to prevent high cost hospitalization, we can afford to deploy many Connectors and aim them into any community where our data shows a pattern of high emergency room use for conditions we know can be treated in lower cost settings. We call that proactive mercy, and the Connectors are the precision tools designed for just that. To date, the Connectors have had more than 1,300 encounters with people in need.

The use of Connectors echoes the radical intelligence that created the hospital in the first place. In 1922, North Carolina Baptists said the hospital would “never be far from the churches.” Brian Davis, of the NC Baptist Convention, notes that although the titles and assignments differ in our modern world, the founders of the hospital envisioned a nursing corps that would do much of the same kind of work and ministry as the Connectors.

The Connectors team at Wake Forest Baptist is led by Jeremy Moseley, Director of Community Engagement for the Division of FaithHealth. He explains that FaithHealth — including, but not limited to, the Connectors and their volunteers — is becoming “the 911 response for both providers and patients for some of the psychological, social and spiritual ills that patients are facing within the community.

“The goal continues to be to decrease costs over the long run by limiting non-emergency ED visits and increasing access to outpatient medical and community-based services, in addition to connecting people to compassionate communities of faith.”

Welcome to the 21st century.